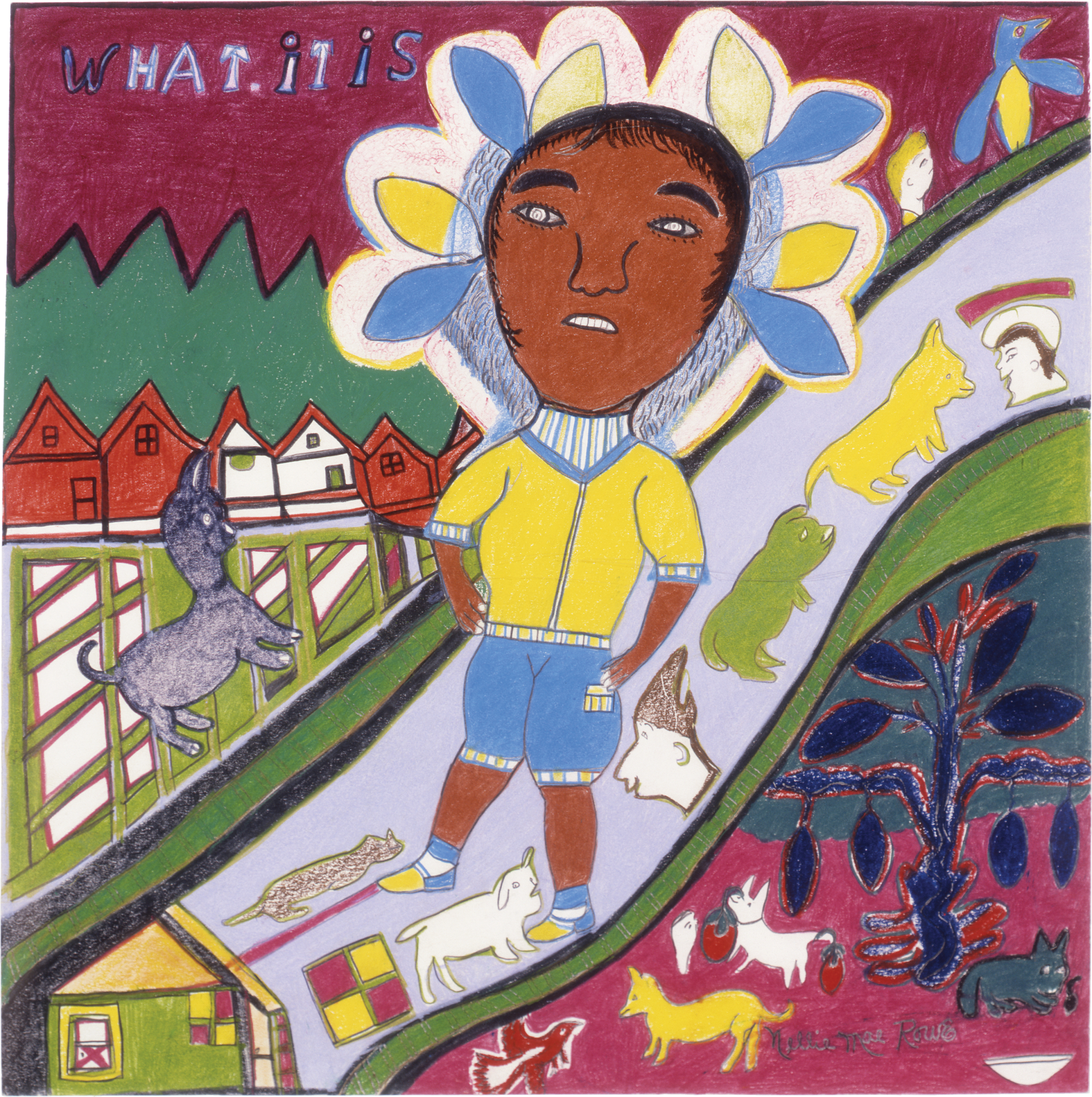

Nellie Mae Rowe

About the Artist

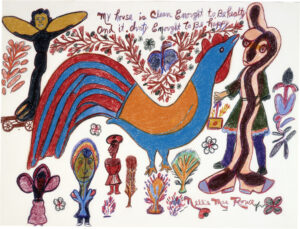

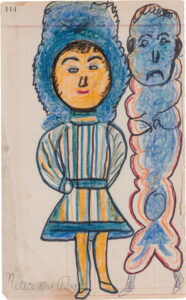

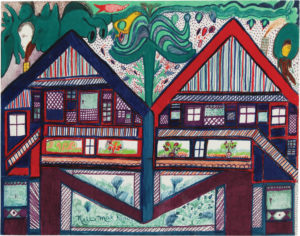

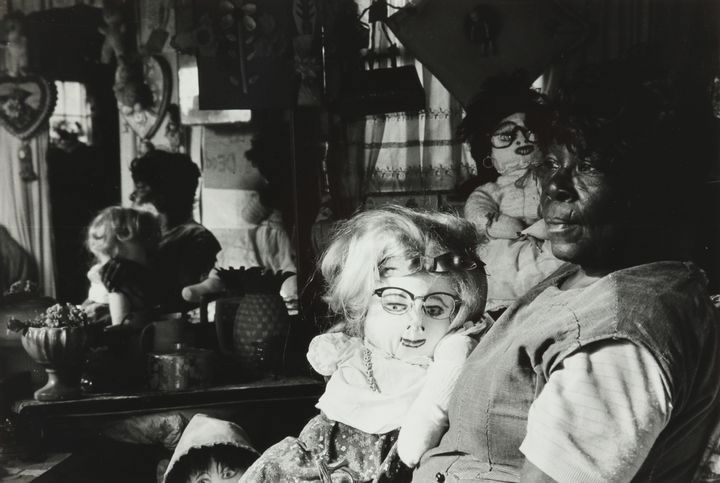

During the last fifteen years of her life, Nellie Mae Rowe lived on Paces Ferry Road, a major thoroughfare in Vinings, Georgia, and welcomed visitors to her “Playhouse,” which one guest described as a “wonder of the land” in one of the many guestbooks the artist began keeping in the early 1970s. Rowe decorated her house with found-object installations, handmade dolls, chewing-gum sculptures, and hundreds of drawings, which she displayed in books, lined up on ledges, and hung cheek by jowl along the walls.

Rowe was born as the ninth of ten children to Sam Williams and Louella Swanson Williams. Although official documentation cannot confirm the exact date of her birth, she said she was born on July 4, 1900—a birthday whose significance as Independence Day of the turn of the century indicates the esteem Rowe held for her life and her relationship to freedom.

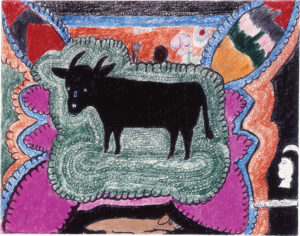

The Williamses rented a farm in Fayetteville, Georgia, earning income primarily from farming cotton and maintaining other crops as well as a small group of livestock to keep their family well fed. Rowe attended school, and one of her teachers told her father, “If she had the chance, she [could] be an artist,” but she only managed to create art around the corners of the days she spent laboring on the farm. She married Ben Wheat in her teens and moved to Vinings, a growing suburb of Atlanta in 1930. After Wheat passed away in 1936, she wed Henry Rowe and settled with him into the home on Paces Ferry Road where she would remain for the rest of her life. By then she had begun working in the home of the Smiths, a White family who lived nearby. With her independent income from domestic labor, she was able to support herself after Henry made her a widow for a second time, and she decided not to remarry. “I lived a good little life and after [Henry] died in 1948 I said, ‘no more foolin” around, no more violin’, no more marryin’. I’m going to get back to my playhouse. I decided I kept house long enough, I don’t want to be bothered by nobody ’cept ’self.”

Over the next twenty years, Rowe dabbled in a return to art making, but it was not until she stopped working for the Smiths—most likely by the end of 1968—that she began drawing and decorating her home and yard with abundance. She cherished the state of creativity and freedom she hardly got to experience as a girl, and she used this long-awaited period of liberation from care and service to reclaim it: “Now I’m going to get back to when I was a little gal playing in the yard, playing in my playhouse,” she said. By 1971, she had richly decorated her yard with garlands, naturally blooming and artificial plants, handmade dolls, and sculptures and installations made from a wide array of reused materials, and several photographers began capturing her portrait amid the lively scene of her Playhouse. In 1973, she was the subject of a profile in the city’s major newspaper, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, which contributed to a rise in the number of visitors she received daily.

After her Playhouse became an Atlanta attraction, she began to exhibit her art in other settings, beginning with Missing Pieces: Georgia Folk Art, 1770–1976, a traveling exhibition that brought attention to several Southern self-taught artists, including Rowe and Howard Finster. Judith Alexander, pioneering Atlanta art dealer, saw Rowe’s work at that time, but it wasn’t until she encountered some of Rowe’s dolls in a group exhibition at the Nexus Artists Cooperative two years later that she became truly enamored with Rowe’s work. She gave Rowe her first solo exhibition in 1978 and arranged for her debut in New York City at the Parsons-Dreyfuss Gallery the following year. In 1980, the High Museum of Art acquired its first piece by Rowe.

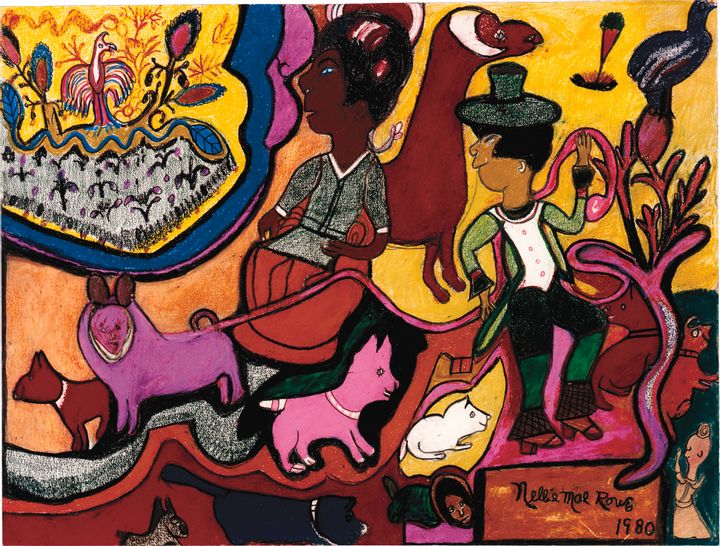

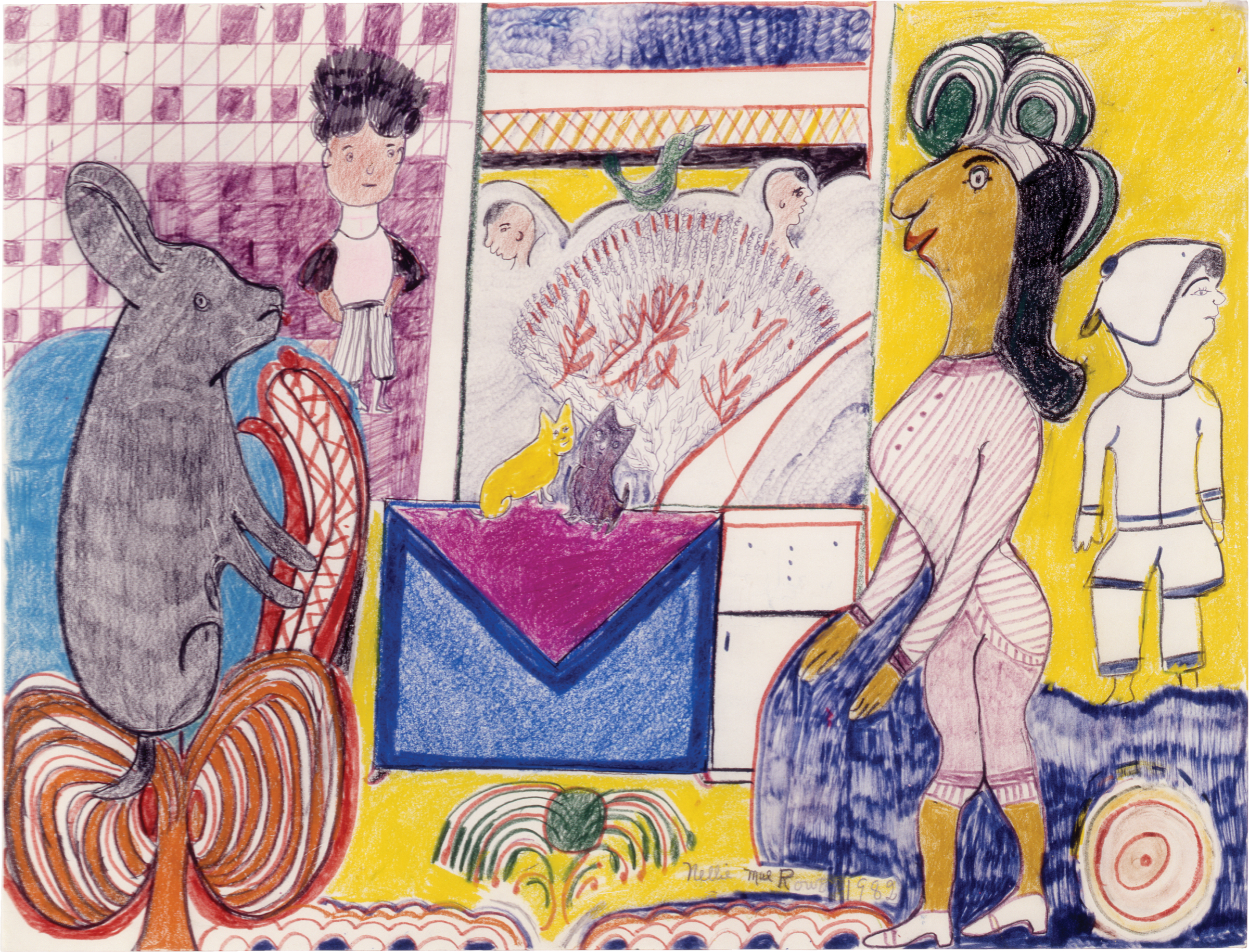

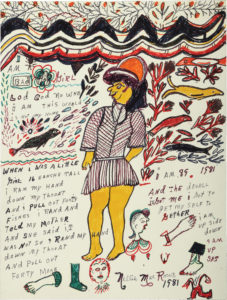

Rowe enjoyed these successes and continued to draw, now on larger, acid-free paper, making many of her most complex compositions. In November 1981, she received a diagnosis of multiple myeloma that would take her life the following year. She did, however, live long enough into 1982 to see her work celebrated on an unprecedented scale both locally and nationally, as she was featured in a one-woman exhibition at Spelman College; her work was also included in Corcoran Gallery of Art’s groundbreaking 1982 exhibition, Black Folk Art in America, 1930–1980.

Rowe approached the end of her life with spiritually inspired optimism. “I feel like I’m growing stronger because I’m serving the Lord, and I thank Him for everything. Letting me stay here this long, living down here on love and land, for this world is not my home. My home is on high and I’m going to reach it one day,” she said. Though she had a large, loving family, she was the only one of her sisters not to have children, and she considered the art she would leave behind as the primary source of her legacy. “All my doll, chewing gum sculptures, everything will be something to remember Nellie. If you will remember me I will be glad and happy to know that people have something to remember me by when I have gone to rest,” she said.

“All my doll, chewing gum sculptures, everything will be something to remember Nellie. If you will remember me I will be glad and happy to know that people have something to remember me by when I have gone to rest.”

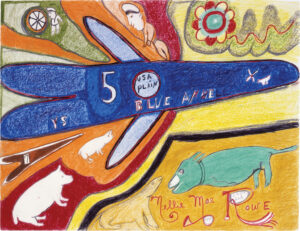

Works by Nellie Mae Rowe

About the Project

In the fall of 2021, the High Museum of Art opened Really Free: The Radical Art of Nellie Mae Rowe and published a catalogue of the same name on the occasion of the exhibition. Both of those projects, as well as the suite of digital resources provided here, celebrate the High’s leading collection of Rowe’s work, which today numbers more than two hundred pieces. The Museum began collecting Rowe’s extraordinary drawings during the artist’s lifetime, and between 1998 and 2003, Rowe’s friend and art gallerist, Judith Alexander, gifted the Museum the majority of its collection. This site offers a variety of ways to virtually experience different dimensions of the exhibition and its related programming, look more closely at Rowe’s life and artworks, and explore multimedia content from the exhibition’s curator and other catalogue contributors.